Disclaimer – This post is in no way trying to promote dark tourism. It is a visual diary of my experience in 2017, in Fukushima’s nuclear fallout zones. Radiation exposure should not be taken lightly.

I remember waking up on the morning of March 11th, 2011, sitting on the couch in my home in Mumbai, glued to the news channel. An earthquake of 9.0 magnitude hit the Tōhoku region of Japan triggering a tsunami. More than 15,000 lives were lost in the floods and destruction. Adding to the misery was the failure of the cooling pumps at Fukushima’s Daichii Nuclear Power Plant. This was the direct cause of the tsunami that flooded over the nuclear plant’s wall of defence, leading to the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

I sat there watching, feeling awful for the disaster that struck a country I admired so much. Little did I know that 6 years later, I would be witnessing the aftermath of Fukushima’s nuclear disaster with my own eyes.

Why Did I Go To Fukushima?

Growing up, I was deeply fascinated by all things abandoned and obscure. So, it would be a lie to say that a hint of morbid curiosity wasn’t one of the reasons that first led me to visit the areas of nuclear fallout. But, it wasn’t the main motivation.

In 2017, I travelled to Japan to volunteer at Japan Cat Network, an animal rescue organization in the snowy countryside town of Inawashiro, Fukushima.

Residents in the immediate area struck by the tsunami and nuclear disaster were forced to evacuate. They had no choice but to leave behind their beloved animals. JCN took up the responsibility of rehoming and caring for as many of those animals as possible.

Inawashiro, Fukushima

The earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima’s nuclear disaster didn’t directly cause much harm to Inawashiro.

During my time off at the volunteer house, I’d walk around town taking photos. I’d take snapshots of everything, from the mountains, streets, alleys, toris, people, and animals.

This was back in 2017, in a world where the 2020 pandemic didn’t exist.

Any time the locals spotted me out and about, they invited me into their homes. Sometimes for a cup of tea with cookies, other times for a fish – which I politely declined. With my broken Japanese, we’d somehow manage to communicate.

They were curious about the tiny brown girl carrying a big camera, wearing shoes that weren’t meant for the snowy Inawashiro streets.

Sometimes — when their sweet English matched my level of Japanese — we would have complex conversations. They expressed their sadness towards the people that had to leave their homes in 2011. They were angry with the way the government was handling the whole ordeal.

Such weekly exchanges led me to want to go see the abandoned towns myself.

Witnessing the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster Zones

I did my research and reached out to several educational organizations that offered tours to strengthen the anti-nuclear sentiment following Fukushima’s nuclear disaster. There were some, but all in Japanese.

That’s when I found an English-speaking Tokyo local with strong ties to Fukushima — let’s call him Mr. Y. A few emails later, it was decided that I would join him and two other foreigners the next day. The plan was to drive around areas on the fringe of the exclusion zone.

I left Inawashiro at night and made my way to Iwaki, where I stayed with Tada and his lovely parents in their traditional home.

The next morning, Mr. Y picked me up from the train station of Iwaki.

With me on the exploration drive, along with Mr. Y, were a movie director and a journalist. The director was working on a documentary about the Fukushima Nuclear Disaster and came to do research. The three of us listened intently, as Mr. Y told us the cause and effect of Fukushima’s nuclear disaster.

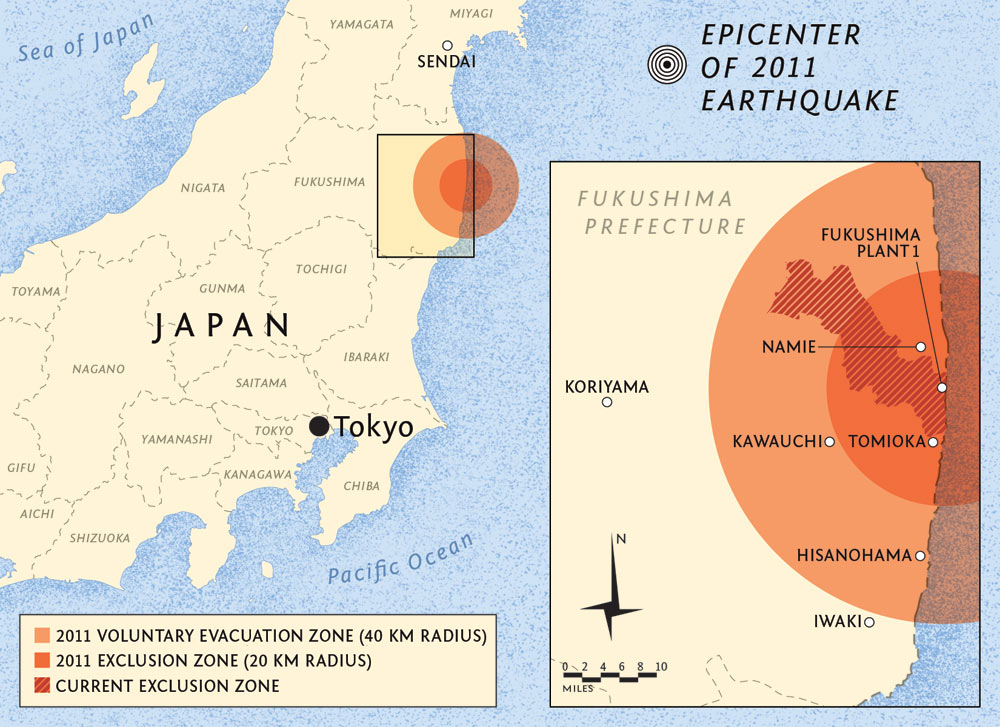

Fukushima Nuclear Disaster Exclusion Zones

We drove around the towns of Tomioka, Okuma, Futaba, and Namie. Some of these areas were opening up and allowing their residents to come back home. Others were strictly off-limit due to the high radiation levels. These spots were a part of the no-go exclusion zones.

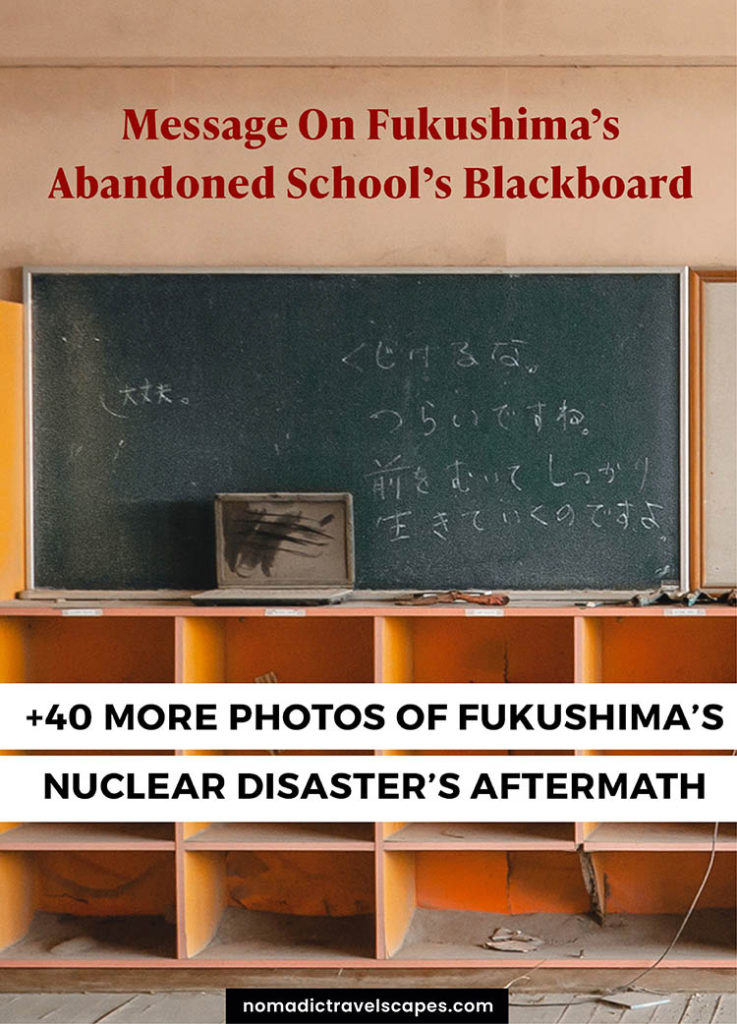

Ukedo Elementary School, Namie

This now abandoned structure stands at less than 500m from the shore. It’s within the 20-kilometre exclusion radius from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

It has been decided that the school is going to remain preserved, to serve as a memory. To remind people of the fragility of life and the importance of roots.

大丈夫

It’s ok. Don’t be afraid. No need to worry.

くじけるな

Never give up. Hang in there.

つらいですね

It’s painful. I know it’s hard for you.

前をむいてしっかり生きていくのですよ

Forward to live by. Live possibly with keeping your feet on the ground.

That’s the message on this blackboard of the classroom, possibly written by rescue workers. Laptops remain untouched since the day the people evacuated.

On March 11th, 2011 after the tsunami hit, authorities instructed the students to dash towards the highway on the opposite side of a nearby mountain range.

Time has stood still, literally and figuratively. The clock is stuck at 15:38. That was the exact moment when the tsunami hit and the building lost power.

Abandoned Family Mart, Okuma

Things are strewn about since the day the town was evacuated. Untouched and collecting dust were magazines, products, and even money.

Abandoned Marine House, Futaba

This highly contaminated marine house was devasted due to the earthquake and tsunami. Notice the time on the clock here too? Same as the Ukedo Elementary school, time stood still at 15:38.

In many of these places, the tsunami has done damage and the aftermath of Fukushima’s nuclear disaster has prevented clean up.

Places Frozen In Time

Before the nuclear incident, a large chunk of the town population living near the reactors were proud of their town’s nuclear energy. Many owners — such as the ones of Parlor Atom—were inspired by the power plants for business names.

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station

As we got closer to Fukushima’s Daiichi Nuclear Powerplant, the police stopped our car and politely requested us to turn back.

Daiichi was set up in the 1970s. For a long time, it helped the citizens of Okuma and Futaba economically through the benefits of its nuclear power.

Daini Nuclear Power Station was the second power plant in Fukushima. Daiichi’s disaster caused a shutdown of Daini as a preventive measure.

Ghost Towns With Empty Streets

Cherry Blossom Tunnel

We ended our visit to Fukushima with a walk around Tomioka’s cherry blossom “tunnel”. The street too was closed for a long time. In the sakura season of 2017, it was allowed to reopen. In the grim scenario, the pink blossoms were a welcoming sight for the locals.

Here, I met a controversial man, who in many ways had inspired me to go to Fukushima and help the animals in the first place. Mr. Naoto Matsumura – The Radioactive Man. After the nuclear disaster, he stayed behind to help the animals in Fukushima’s nuclear disaster zones.

Fukushima Today, March 11 2021

Today marks a decade since the disasters. My friends in Fukushima tell me that while a lot has changed for the better, unfortunately, many other important things still haven’t. The government has done its best to encourage ex-citizens to go back to their homes. Locals are, however, still pretty reluctant to return home. Some have already built a life outside of Fukushima and do not wish to uproot for the second time. Others are afraid of the dangers of nuclear fallout.

I would rather continue living outside Fukushima. If I came back, the focus of my everyday life would always be the disaster. A life full of Geiger counters and sad news on the bulletin is no way to live.

Photographer / Fukushima Ex-Resident

Let’s not forget that there’s so much more to Fukushima than the nuclear zones. There’s unbelievable magic in the snowy peaks of Mount Bandai. The samurai town of Aizu Wakamatsu is also one of a kind. I also truly believe that the kindest people live in Fukushima. Despite going through a tragic disaster, conversations with them will help you reinvent the concepts of hope and forgiveness.

Like This Post? Pin It!

Interested in taking an educational tour to witness the dangers and aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear disaster?

Reach out to The Real Fukushima or book via one of the Viator tours below